From Sinai to Zion: The Living Continuity of Revelation

In ancient times, the most authoritative body of Jewish law was the Sanhedrin, a council of holy sages that convened in the Lishkat HaGazit, a special chamber on the Har HaBayit. From this sacred space, they issued decisive halachic rulings and clarified matters of dispute for the entire nation.

At first glance, their location might seem like a practical choice. Since the Temple Mount served as the spiritual center and gathering point for Jews across Eretz Yisrael, it would make logistical sense for the Sanhedrin to be based there. But the significance of the Lishkat HaGazit goes far deeper.

When the Sanhedrin was forced to leave the Har HaBayit forty years prior to the destruction of the Temple, they lost their authority to implement capital punishment (see Rambam, Hilchot Sanhedrin 14:12-13). This loss of jurisdiction reflects something far more fundamental. Severed from the Mikdash, the Sanhedrin‘s stature and spiritual potency were diminished.

But why? The same brilliant scholars remained. Why should the physical location of their deliberations affect their authority?

To answer this question, we need to delve more deeply into Matan Torah and the spiritual function of the Mikdash.

We often speak of the Torah being given in its entirety to Moshe Rabbeinu at Har Sinai. But in reality, the process of Matan Torah was far more extended and complex. For instance, Moshe could not have written about the rebellion of Korach or the zealotry of Pinchas while still at Sinai—they had not yet occurred. The entire Sefer Devarim was delivered only at the end of Moshe’s life.

In truth, Matan Torah was not a one-time event. It spanned the entire forty years of desert wandering. At Sinai, Moshe recorded Bereishit and most of Shemot up to the construction of the Mishkan. The rest of the Torah was written gradually, as events unfolded, and completed just before Moshe’s death (see the Gemara Gittin 60a with Rashi; Ramban’s introduction to Bereishit).

Though only part of the written Torah was received at Sinai, all of it is infused with the Sinai experience. The Ramban explains (Shemot 25:2) that the command to build the Mishkan followed immediately after the revelation at Sinai because God desired His Presence to remain palpably within the Jewish camp. What began at Sinai was meant to continue.

Just as Moshe Rabbeinu ascended Har Sinai to receive the word of God, he later entered the Mishkan to hear the Divine voice emanating from between the Keruvim atop the Aron HaKodesh.

The experience of Matan Torah didn’t end; it became mobile. The people encamped around the Mishkan just as they had encircled the mountain, learning Torah as Moshe transmitted the ongoing word of God from the Ohel Moed.

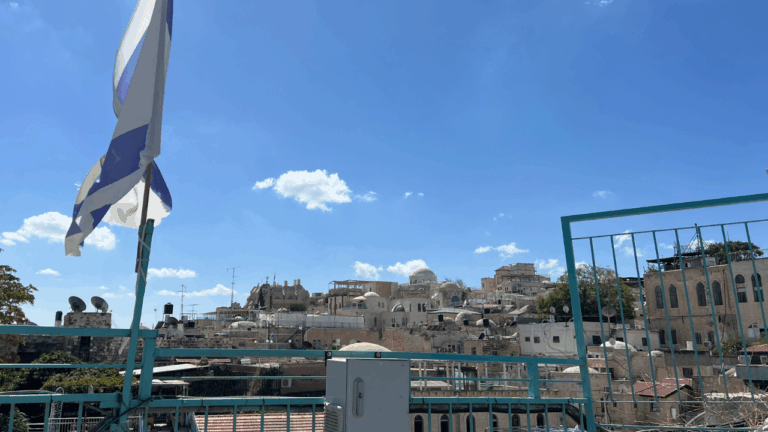

But the revelation didn’t stop in the desert. As the Ramban notes, this “portable” Har Sinai experience culminates in Jerusalem. The Beit HaMikdash becomes the fixed conduit through which Divine wisdom flows into this world. The spatial structure of the camp in the desert – Machaneh Yisrael, Machaneh Leviya, and Machaneh Shechina – was mirrored in Jerusalem: the city, the Temple Mount, and the Temple itself.

In Sefer HaKuzari (3:39-41), Rebbe Yehudah HaLevi explains that when the Sanhedrin sat in their sacred chamber within the Mikdash, they merited elevated levels of Divine inspiration. In this holy setting, their halachic intuition was not only razor sharp: it was guided by Divine Providence and infused with a spirit of holiness and purity. The Sanhedrin in the Mikdash didn’t merely apply Torah law; they extended the experience of Matan Torah itself. כי מציון תצא תורה ודבר ה’ מירושלים-only through Tzion can Torah emerge in splendor and majesty.

As we approach the day when the Divine voice first echoed from Har Sinai, let us pray for the ultimate continuation of that revelation: the rebuilding of the Beit HaMikdash and the return of the Sanhedrin to their rightful place, where the Torah can once again emerge in glorious splendor, speedily in our days.