Frum or Erlich? Rediscovering What Jerusalem is Truly About

In this week’s haftorah, Yeshayahu HaNavi delivers a stinging rebuke to the Jewish people. As Yerushalayim rebels against Hashem, the navi warns of the looming destruction that faces her. He even compares the Jewish people to Sodom and Amorah.

Tucked within these frightening verses is a stunning rejection of our korbanot and tefillah:

Of what use are your many sacrifices to Me? says Hashem. I am sated with the burnt-offerings of rams and the fat of fattened cattle; and the blood of bulls and sheep and hegoats I do not want. When you come to appear before Me, who requested this of you, to trample My courts?… Your New Moons and your appointed seasons My soul hates, they are a burden to Me; I am weary of bearing [them].

With visceral revulsion, Hashem rejects our avodah and demands teshuvah. How can you offer sacrificeswhen you do not act with righteousness and justice? When you abandon the orphan and the widow, even the most elaborate korban becomes an abomination.

At first glance, this harsh reaction seems shockingly disproportionate. The Torah includes hundreds of mitzvot, and no human being can flawlessly uphold them all. We’re not angels. Of course our interpersonal behavior will sometimes fall short. But why should that invalidate the other mitzvot that we perform? Just because someone struggles with anger doesn’t mean his Shabbat observance is worthless. Why are korbanot so uniquely vulnerable to corruption?

To answer this question, we must first understand what makes korbanos so important in the first place. The Maharal (Nesiv Avodah 1)explains that the whole purpose of a korban is to symbolically hand oneself over to the Ribbono Shel Olam. The animal, its slaughter, and the monetary loss this process entails, represent the individual’s full surrender to Hashem. The korban represents a simple and sincere submission to the Divine will.

But this symbolic gesture means nothing when not accompanied with a genuine dedication to Hashem and His children. When this internal surrender is absent, the outward gesture is not just empty, but disgraceful. It reduces korbanot to a grotesque display of piety, like a lavish “barbecue for God” that has no substance behind it.

Without an authentic surrender to Hashem to accompany it, the korban becomes a twisted expression of misplaced values and overly crude service of Hashem. Even a Sodomite can offer up sacrifices in a despicable

display of “spiritual righteousness” – but his morally vacuous existence reveals that his korban is nothing more than a selfish exhibit of vanity.

As Yeshayahu tells us, the only thing that can redeem Jerusalem from such moral and religious rot is a return to righteous justice. When we shift our focus from ourselves to those who are alone, vulnerable, and downtrodden, our worship becomes real again. It is rooted in the will of God, not our own ego.

The Alter of Slobodka once sharply noted about those who exclusively focus on technical mitzvah observance without a spirit of decency, “A galach (priest) is frum. A Yid must be erlich.”

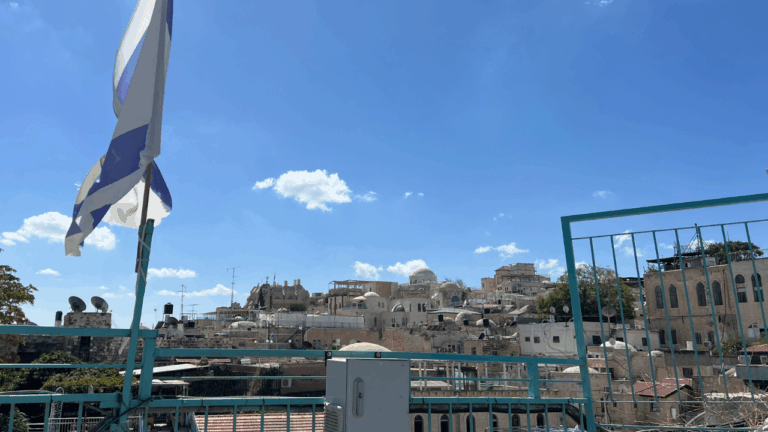

Yerushalayim is the city of erlichkeit – of honest, upright, and authentic service of Hashem. To restore her glory, we must reconnect with the simple righteousness captured by that word. With so much pain and suffering still engulfing the Jewish people, and with Jerusalem’s redemption far from completion, we need to take an honest look in the mirror and ask: is our Divine service and chessed truly dedicated to Hashem and His children, or is it deep down, still about ourselves.